Posted Sep 29, 2022, 2:36 PM

The history of art shows that, whatever the times, it happens that artists find themselves through certain obsessions. The Louis Vuitton Foundation (LVMH group, owner of Echoes) this fall looks at a textbook case: how two extraordinary sensibilities meet several decades apart around their feeling for nature, expressed in a frenetic painting, made in a small corner of Vexin .

The institution is thus offering, until February 27, a dialogue between the paintings of the Frenchman Claude Monet (1840-1926) and those of the American Joan Mitchell (1925-1992). An epicurean dive into these two verves. Suzanne Pagé, artistic director of the museum talks about a “echoing works” accompanied by a “invitation to really look, spending time there”. The confrontation is spectacular, the two artists playing on the visual caress through the colors and on the immersion of the observer.

Let’s start with the eldest. If, as Charles de Gaulle said “Old age is a shipwreck” , there are people for whom it represents a time of apotheosis. This is the case of the impressionist of the first hour, Claude Monet. As he grew old, in his garden in Giverny, where he had lived since 1886, he gave himself to his heart’s content to bring out the smooth hues of his aquatic landscapes. He frees himself from forms, which are literally diluted in his compositions. This is where his sense of polychromy, with the infinite shades of blue, green, yellow and even brown, takes on its full power.

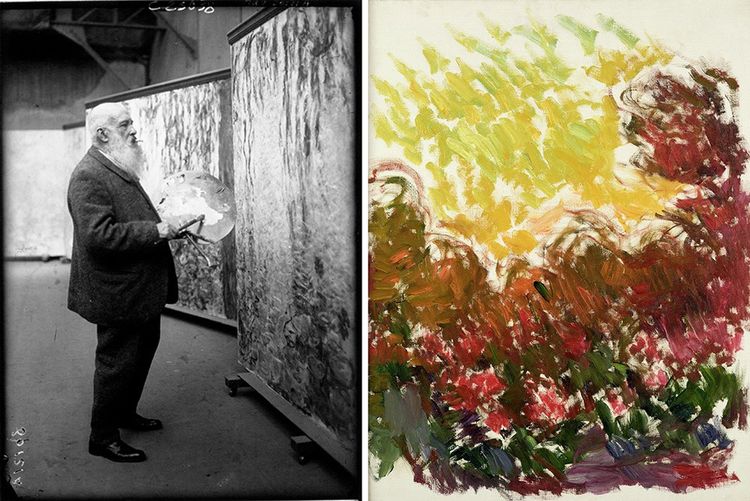

Claude Monet in his studio in Giverny in 1926. On the right: “Le Jardin à Giverny” (1922-26).Source gallica.bnf.fr/BnF/Louis Vuitton Foundation; Marmottan Monet Museum, Paris/Louis Vuitton Foundation

Claude Monet is not an artist whose career can be summed up in a rectilinear creation. From the 1910s, a revolution even occurred at home. There are therefore at least two Claude Monets: that of so-called “classical” Impressionism which has gone down in history with its beautiful flower gardens and its women in large white dresses and another, post-1912, old but still brand new. and completely free.

The first is the one who will give his name to the impressionist movement, with his little painting now in the Marmottan museum in Paris. Print, rising sunwith its 63 cm wide, presents an orange ball reflecting in the water, surrounded by the bluish shadows of the port of Le Havre in 1872. The painting is certainly daring for the time, but the painter takes care to inject it with realistic and precise elements such as what we imagine to be a fisherman on his boat in the foreground, or even, in the background, these cranes and these chimneys which suggest the industrial activity of the city.

The second Claude Monet, even more radical, wrote in 1912 to his art critic friend Gustave Geffroy: “I only know that I do what I can to render what I feel in front of nature and that most often, to manage to render what I feel, I totally forget the most elementary rules of painting, if there are any. In short, I allow many faults to appear in order to fix my feelings. » And it is this Monet who is shown at the Louis Vuitton Foundation in 34 paintings.

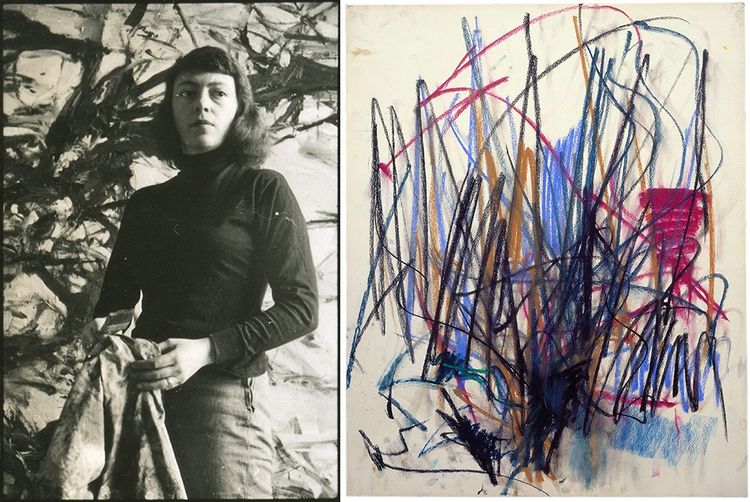

Joan Mitchell, photographed in her New York studio in 1954, a year before she left for France. Right: “Linden”, pastel made in 1978.Rudy Burckhardt/Joan Mitchell Foundation/Louis Vuitton Foundation; The Estate of Joan Mitchell/Louis Vuitton Foundation

To face him, in an obsessive dialogue, there is Joan Mitchell, American painter of the abstract expressionist movement, with her 24 works. In Frank Gehry’s building, on the ground floor, Suzanne Pagé also orchestrated, in around fifty paintings, a retrospective of the painter. Joan and France is a unique story. Raised in a bourgeois family in Chicago, she was able to see the Impressionist masters very early on in her city’s museum, the Chicago Art Institute. In New York, she will be part of the second generation of the abstract expressionist movement. She meets with success at a very young age, but her nature is freedom. So she left in 1955 on the other side of the Atlantic. In Paris, she meets the one who will become her companion and artistic accomplice until 1979, the Canadian painter, Jean Paul Riopelle. It does not seem that she really frequented the artistic scene of the French capital. She preferred to find refuge in the countryside, where, as soon as her means permitted, she bought a house in 1967.

The residence is located in Vétheuil in the Vexin, where, a few meters away, the great Claude Monet lived between 1878 and 1881. And the small town is barely 18 kilometers from Monet’s “kingdom”, Giverny. Contrary to what one might imagine, its installation precisely in Monet’s footsteps is a coincidence. Mitchell will not assume this influence when she seems literally caught up in the painterly expressions of the Impressionist master. She will say, for example, about the colors inspired by Vétheuil: “In the morning, especially very early, it’s purple; Monet has already shown this. Me, when I go out in the morning, it’s purple, I don’t copy Monet. » There is also no doubt that she had the opportunity to admire the cycle of water lilies offered in 1918 by the old master to the French State, which can still be experienced at the Musée de l’Orangerie. The nymphsa.k.a “the Sistine of Impressionism” as the modern painter André Masson called it, were the ferment of a powerful brush of abstraction, feminine and American, that of Joan Mitchell.

Two monumental ensembles

It cannot be said that Joan Mitchell’s inspiration is a literal take on Claude Monet’s style. Certainly the second spoke of the desire to represent “feelings” and the first used the related concept of “feeling”. But first of all they do not belong to the same period. Monet is a child of the XIXe century French and Mitchell a daughter of the turbulent urban America of the XXe. Thus, everyone has their own working method and different objectives which nevertheless lead to results with many common points. In his last years, Monet had a large studio built in Giverny which enabled him to transcribe in giant format the patterns he observed in the garden he had designed himself. Joan Mitchell locks herself up in her studio at night with her dogs. She blasts the music loudly. Alcohol taken in high doses catalyzes his imagination. And she paints in an abstract tone, as Suzanne Pagé explains, “not only things inspired by his daytime observations in the Vexin countryside, but also his memories of childhood especially at the edge of Lake Michigan”.

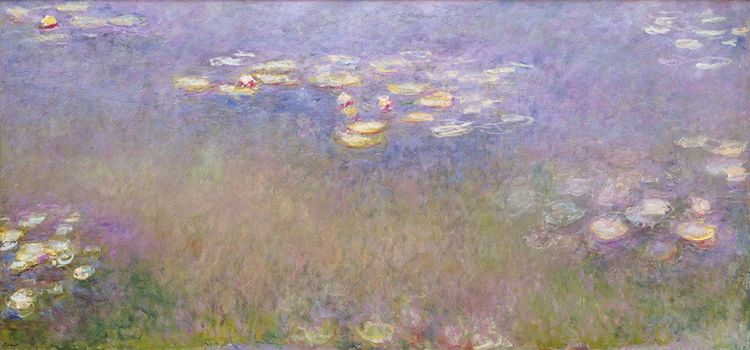

“The Agapanthe” (1915-1926), by Claude Monet, a triptych where each part is 4.2 meters long (here the central panel).Louis Vuitton Foundation

Monet is an old gentleman who achieves physical prowess on his huge canvases, while Mitchell is a former high-level sportswoman, accustomed to grand gestures. Both are obsessed with the effects of light on hues. They play with thick textures and transparency effects. They also share a dominant of blues and greens and the layers of paint are superimposed. The route of the exhibition concludes with two monumental ensembles. Between 1915 and 1926, Monet produced a triptych called Agapanthus, each canvas of which is 4.2 meters long. There are up to eight layers of paint in what specialists call its “great decorations”. But in fact, it is, as usual with the painter, water lilies floating on the surface of the pond in green, bluish and purple tones. The three paintings brought together in Paris now belong to American museums. They had a major impact across the Atlantic on the understanding and influence of this quasi-abstract Claude Monet of recent years, particularly with the abstract expressionist movement.

“La Grande Vallée XIV” (1983), triptych by Joan Mitchell, almost 3 meters long in total.The Estate of Joan Mitchell/Louis Vuitton Foundation

In 1983 and 1984, Joan Mitchell produced a series of 21 paintings in Vétheuil, entitled The Great Valley. His companion left him recently for another woman and his sister has just died. In the night of her studio, Joan struggles with life in bursting colors. Painting is a tool for celebrating existence. Ten paintings from the series are brought together in the Vuitton Foundation exhibition.

“Monet-Mitchell. Dialogue and retrospective”, from October 5 to February 27. www.fondationlouisvuitton.fr

Joan Mitchell, the retrospective

“When she arrived in Vétheuil, her talent blossomed. » Suzanne Pagé, who knew the American painter well, notes a kind of love story between the artist and this corner of Normandy that she adopted in 1967. “I love what I see. I am influenced by the light, the fields. » Born in Chicago in 1925, Joan Mitchell quickly found success in New York in the company of sacred monsters of American painting such as de Kooning and Kline. But as Brancusi would say about his passage through Rodin’s studio, “Nothing grows in the shade of the great oaks. » She must free herself from her friends and American giants. So she leaves for her French adventure. Her gesture is characteristic: she does not cover the canvas but produces colored concentrations through large, measured gestures. The Vuitton Foundation has 13 paintings by Mitchell and the retrospective on the ground floor presents 50.